-by Meredith Poynter

A Rough Ride

I learned early that this journey to heal childhood trauma is a bit of a rollercoaster ride. How do we participate in that ride and yet remain resilient? I love my child with all my heart, but know if I don’t have the right mental tools, she can be an emotional vampire. Her mind has been, and sometimes still is, a chaotic storm. She latches on to me as her stable rock in that storm, which over the years, has taken a toll. I have sometimes felt like a shell of the person I once was. But I’d like to think that I am better, that I am healing now too.

I think good parents carry around a great deal of unnecessary guilt. I know I do. Even though I’ve done my best to parent my daughter well, I feel any mistakes I’ve made were not only a waste of precious time but counter-productive. I’ve spent the better of the last 15 years building a relationship with her, but it remained fragile. It would not take too much to sever it. This has meant learning to parent her in a way that always puts our bond and relationship first.

Why is that so important? Ultimately, my goal is for her to learn how to make good decisions for herself. Therefore, I must first teach her how to bond with me, so that she can learn to bond with others and so that she grows receptive to my influence. That way, I can guide her when necessary. One of the most important realizations I ever had was that I can’t MAKE her do ANYTHING. Believe me when I say I tried. The blowback was painful. I think some parental guilt surfaces when our child makes that poor decision. We feel like we are the ones that failed because we weren’t able to prevent it. In reality, though, I can control only my behavior. She might react a certain way to what I say or do, but that’s the limit of my control.

Failing Forward

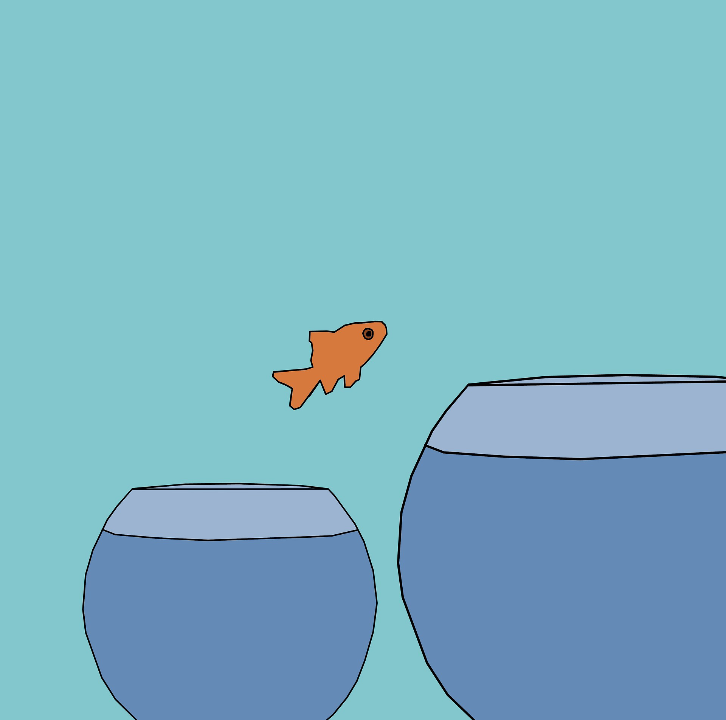

I first encountered this concept of “Failing Forward” several years ago in a business seminar on competitiveness and innovation. But a great deal of what was said really spoke to me as a parent of a child diagnosed with Reactive Attachment Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. This expression, “Failing Forward” became a new favorite. It means accepting failures as part of the learning process and making the failure meaningful by finding opportunities to come up with new ideas or opportunities to move forward.

For my daughter, her mental health struggles impact her decision-making. The hurdles loom much larger. I tend to obsess over what I can do to help her until I remember that she has to work hard at this too. Then I debate in my head if she is incapable or if she is just unwilling. Which leads me back to the beginning of this ongoing cycle of wondering what I can do to help her.

Natural consequences

I have learned that the best way for her to experience failing forward is natural consequences. Consequences related to school stayed at school, including those involving homework. Any additional consequence I gave her would be a punishment, which would have undermined my relationship with her. I advocated for her needs behind the scenes, I showed interest in her school work, but I did not judge her for her choices. This helped strengthen and preserve the relationship. Regardless of the cause, even now, I empathize with the fallout of not doing what she needs to do, and celebrate the positive results when she does.

I myself practiced failing forward big time by learning never to ground or punish, how to reframe things so I wouldn’t have to tell her “no.” I can’t imagine parenting any other way than I do now, but it wasn’t always that way. Can you imagine telling a random parent on the street that he or she may not ground or punish their child? At first it feels like someone takes away all your tools to parent. And after I made the change, people criticized me.

Natural consequences make her own her behaviors and instill responsibility for her choices. It effectively combats some of the behaviors and delays that can come with childhood trauma. The biggest challenge as a parent in this method is giving up the power, even though we never really had it to begin with. We have to let the action and subsequent consequence, not the parent, teach the child. The parent sets the boundaries and supports the child. It would work for any child, from a calm, centered, regulated child, to child diagnosed with RAD.

From challenge to opportunity

I’ve learned that my daughter tends to make the biggest strides when she has to deal with the repercussions of her mistakes. Some of these mistakes, I can live with. But there are a few that I really wish never happened, that that have had permanent impact on members of our family including herself. Even so, the more severe her action, the larger the consequence, the more she has moved forward, is always failing forward.

Even though I still struggle with parental guilt and letting go of control, I’ve learned that her poor choices have been one of her best teachers. She owns them, has navigated through the consequences, learned from them, and persevered. I look at these events and challenges as opportunities. “Failing Forward” has been a large part of her journey, from nearly spending her teens in jail, to being expelled from high school, to starting her fourth year of college today. Her journey hasn’t been typical, but it has moved forward.